How did the WannaCry ransomworm spread?

Adam McNeil

Adam McNeil

Security researchers have had a busy week since the WannaCry ransomware outbreak that wreaked havoc on computers worldwide. News of the infection and the subsequent viral images showing everything from large display terminals to kiosks being affected created pandemonium in ways that haven’t been seen since possibly the MyDoom worm circa 2004.

News organizations and other publications were inundating security companies for information to provide to the general public – and some were all too happy to oblige. Information quickly spread that a malicious spam campaign had been responsible for circulating the malware. This claim will usually be a safe bet, as ransomware is often spread via malicious spam campaigns. Admittedly, we also first thought the campaign may have been spread by spam and subsequently spent the entire weekend pouring through emails within the Malwarebytes Email Telemetry system searching for the culprit. But like many others, our traps came up empty.

Claims of WannaCry being distributed via email may have been an easy mistake to make. Not only was the malware outbreak occurring on a Friday afternoon, but around the same time a new ransomware campaign was being heavily distributed via malicious email and the popular Necurs botnet. We recently wrote about the Jaff ransomware family and the spam campaign that was delivering it.

Some may have seen the rash of news occurring on their feeds, an uptick in ransomware-themed document malware in their honeypots, and then jumped to conclusions as a way to be first with the news.

But here at Malwarebytes we try not to do that. And now after a thorough review of the collected information, on behalf of the entire Malwarebytes Threat Intelligence team, we feel confident in saying those speculations were incorrect.

Indeed, the ‘ransomworm’ that took the world by storm was not distributed via an email malspam campaign. Rather, our research shows this nasty worm was spread via an operation that hunts down vulnerable public facing SMB ports and then uses the alleged NSA-leaked EternalBlue exploit to get on the network and then the (also NSA alleged) DoublePulsar exploit to establish persistence and allow for the installation of the WannaCry Ransomware.

We will present information to support this claim by analyzing the available packet captures, binary files, and content from within the information contained in The Shadow Brokers dump, and correlating what we know thus far regarding the malware infection vector.

Here’s what we know

EternalBlue

EternalBlue is an SMB exploit affecting various Windows operating systems from XP to Windows 7 and various flavors of Windows Server 2003 & 2008. The exploit technique is known as heap spraying and is used to inject shellcode into vulnerable systems allowing for the exploitation of the system. The code is capable of targeting vulnerable machine by IP address and attempting exploitation via SMB port 445. The EternalBlue code is closely tied with the DoublePulsar backdoor and even checks for the existence of the malware during the installation routine.

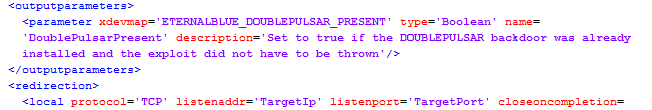

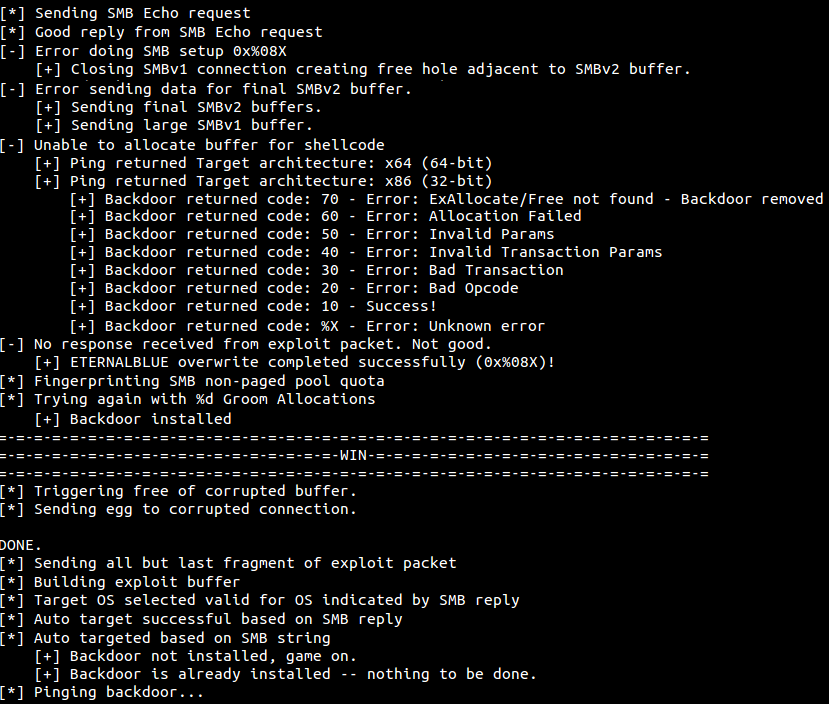

Bits of information obtained by reviewing the EternalBlue-2.2.0.exe file help demonstrate the expected behavior of the software. The screenshot above shows that the malware:

- Sends an SMB Echo request to the targeted machine

- Sets up the exploit for the target architecture

- Performs SMB fingerprinting

- Attempts exploit

- If successful exploitation occurs, WIN

- Pings the backdoor to get an SMB reply

- And if the backdoor is not installed, it’s game on!

The ability of this code to beacon out to other potential SMB targets allows for propagation of the malicious code to other vulnerable machines on connected networks. This is what made the WannaCry ransomware so dangerous. The ability to spread and self-propagate causes widespread infection without any user interaction.

DoublePulsar

DoublePulsar is the backdoor malware that EternalBlue checks to determine the existence and they are closely tied together.

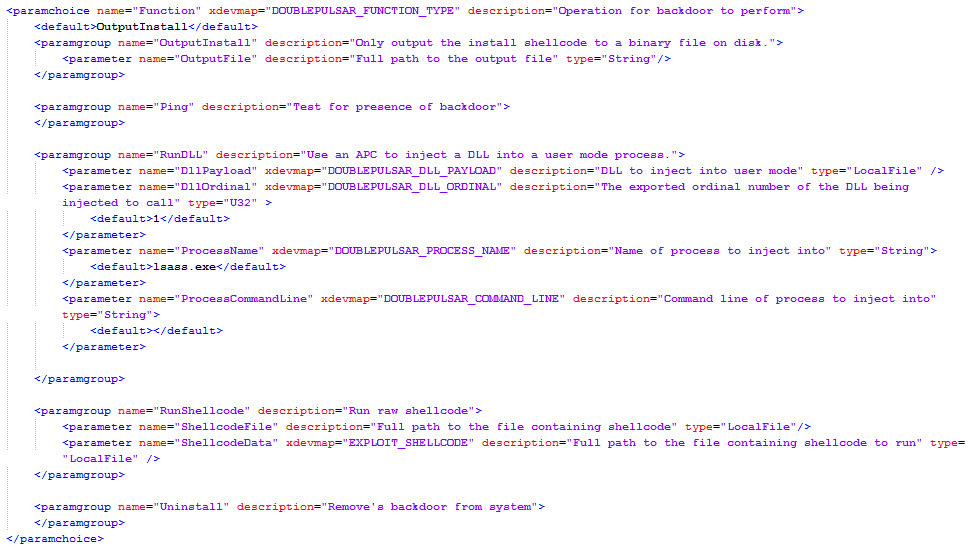

This particular malware uses an APC (Asynchronous Procedure Call) to inject a DLL into the user mode process of lsass.exe. Once injected, exploit shellcode is installed to help maintain persistence on the target machine. After verifying a successful installation, the backdoor code can be removed from the system.

DoublePulsar Parameters

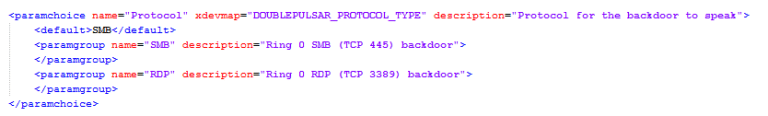

The purpose of the DoublePulsar malware is to establish a connection allowing the attacker to exfiltrate information and/or install additional malware (such as WannaCry) to the system. These connections allow an attacker to establish a Ring 0 level connection via SMB (TCP port 445) and or RDP (TCP port 3389) protocols.

A high-level view of a compromised machine in Argentina (186.61.18.6) that attacked the honeypot:

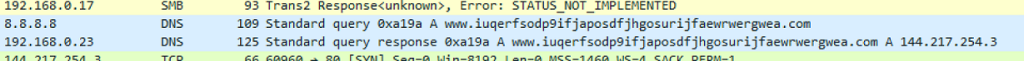

The widely publicized kill-switch domain is present in the pcap file. As was reported, the malware made a DNS request to this site. Until @MalwareTech inadvertently shut down the campaign by registering the domain, the malware would use this as a mechanism to determine if it should run.

The SMB traffic is also clearly visible in the capture. These SMB requests are checking for vulnerable machines using the exploit code above.

SMB Requests

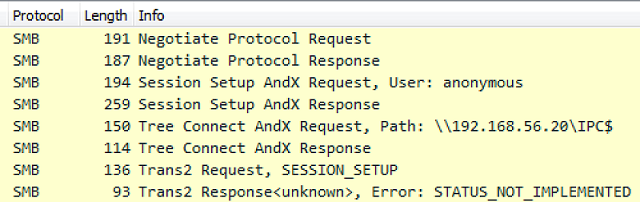

The exploit sends an SMB ‘trans2 SESSION_SETUP’ request to the infected machine. According to SANS, this is short for Transaction 2 Subcommand Extension and is a function of the exploit. This request can determine if a system is already compromised and will issue different response codes to the attacker indicating ‘normal’ or ‘infected’ machines.

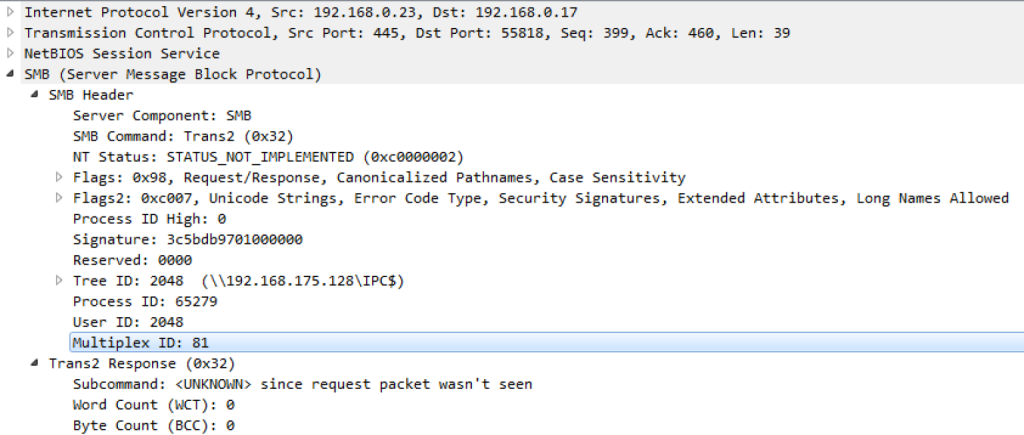

Diving into the .pcap a bit more, we can indeed see this SMB Trans2 command and the subsequent response code of 81 which indicates an infected system. If the attacker receives this code in response, then the SMB exploits can be used as a means to covertly exfiltrate data or install software such as WannaCry.

Trans2 Multiplex ID

Putting it all together

The information we have gathered by studying the DoublePulsar backdoor capabilities allows us to link this SMB exploit to the EternalBlue SMB exploit. It’s really not hard to do so as both were patched. Without otherwise definitive proof of the infection vector via user-provided captures or logs, and based on the user reports stating that machines were infected when employees arrived for work, we’re left to conclude that the attackers initiated an operation to hunt down vulnerable public facing SMB ports, and once located, using the newly available SMB exploits to deploy malware and propagate to other vulnerable machines within connected networks.

Developing a well-crafted campaign to identify just as little as a few thousand vulnerable machines would allow for the widespread distribution of this malware on the scale and speed that we saw with this particular ransomware variant.

So what did we learn?

Don’t jump to conclusions. Malware analysis is difficult and it can take some time to determine attribution to a specific group, and/or to assess the functionality of a particular campaign – especially late on a Friday (which BTW, can all you hackers quit making releases on Fridays!!). First, comes stopping the attack, second comes analyzing the attack. Remember, patience is a virtue.

Update, update, UPDATE! Microsoft released patches for these exploits prior to their weaponization. Granted, patches weren’t available for all Operating Systems, but the patch was available for the vast majority of machines. This event even forced Microsoft to release a patch for the long-ago EOL Windows XP – which gets back to the first thing that was said. UPDATE! Why are there still machines on XP!? These machines are vulnerable (beyond this attack) to the ransomware functionality of this attack and they need to be updated.

Disable unnecessary protocols. SMB is used to transfer files between computers. The setting is enabled on many machines but is not needed by the majority. Disable SMB and other communications protocols if not in use.

Network Segmentation is also a valuable suggestion as such precautions can prevent such outbreaks from spreading to other systems and networks, thus reducing exposure of important systems.

And finally, don’t horde exploits. Microsoft president Brad Smith used this event to call out the ‘nations of the world’ to not stockpile flaws in computer code that could be used to craft digital weapons.

That reminds me of an article I wrote a few years ago (and which was substantially cut for length) about Hacking Team and the government sanctioned use of exploits.

Hack Me: A Geopolitical Analysis of the Government Use of Surveillance Software

I guess things haven’t changed…

Cybercrime Has Gone Machine-Scale

AI is automating malware faster than security can adapt.

Get the facts Read the 2026 State of MalwareCybercrime Has Gone Machine-Scale

AI is automating malware faster than security can adapt.

Get the facts Read the 2026 State of Malware