Analyzing malware by API calls

Over the last quarter, we’ve seen an increase in malware using packers, crypters, and protectors—all methods used to obfuscate malicious code from systems or programs attempting to identify it. These packers make it very hard, or next to impossible to perform static analysis. The growing number of malware authors using these protective packers has triggered an interest in alternative methods for malware analysis.

Looking at API calls, or commands in the code that tell systems to perform certain operations, is one of those methods. Rather than trying to reverse engineer a protectively packed file, we use a dynamic analysis based on the performed API calls to figure out what a certain file might be designed to do. We can determine whether a file may be malicious by its API calls, some of which are typical for certain types for malware. For example, a typical downloader API is URLDownloadToFile. The API GetWindowDC is typical for the screen-grabbers we sometimes see in spyware and keyloggers.

Let’s look at an example to clarify how this might be helpful.

Trojan example

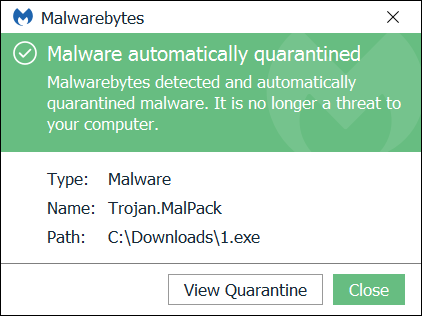

Our example is a well-known Trojan called 1.exe with SHA256 0213b36ee85a301b88c26e180f821104d5371410ab4390803eaa39fac1553c4c

The file is packed (with VMProtect), so my disassembler doesn’t really know where to start. Since I’m no expert in reverse engineering, I will try to figure out what the file does by looking at the API calls performed during the sandboxed execution of the file.

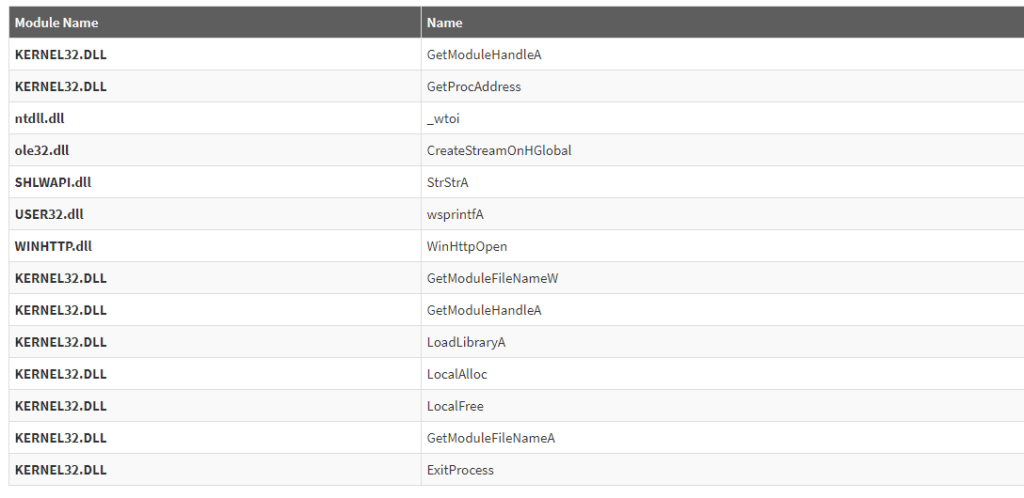

This is the list of calls that we got from the sandbox (Deepviz):

For starters, let’s have a look at what all these functions do. Here’s what I found out about them on Microsoft:

Retrieves a module handle for the specified module. The module must have been loaded by the calling process. GetModuleHandleA (ANSI)

Retrieves the address of an exported function or variable from the specified dynamic-link library (DLL).

Convert a string to integer.

CreateStreamOnHGlobal function

This function creates a stream object that uses an HGLOBAL memory handle to store the stream contents. This object is the OLE-provided implementation of the IStream interface.

Finds the first occurrence of a substring within a string. The comparison is case-sensitive. StrStrA (ANSI)

Writes formatted data to the specified buffer. Any arguments are converted and copied to the output buffer according to the corresponding format specification in the format string. wsprintfA (ANSI)

This function initializes, for an application, the use of WinHTTP functions and returns a WinHTTP-session handle.

Retrieves the fully qualified path for the file that contains the specified module. The module must have been loaded by the current process. GetModuleFileNameW (Unicode)

Loads the specified module into the address space of the calling process. The specified module may cause other modules to be loaded. LoadLibraryA (ANSI)

Allocates the specified number of bytes from the heap.

Frees the specified local memory object and invalidates its handle.

Retrieves the fully qualified path for the file that contains the specified module. The module must have been loaded by the current process. GetModuleFileNameA (ANSI)

Ends the calling process and all its threads.

The key malicious indicators

Not all of the functions shown above are indicative of the nature of an executable. But the API WinHttpOpen tells us that we can expect something in that area.

Following up on this function, we used URL Revealer by Kahu Security to check the destination of the traffic and found two URLs that were contacted over and over again.

GET http://twitter.com/pidoras6

POST http://www.virustotal.com/vtapi/v2/file/scan

This POST is what the VirusTotal API expects when you want to submit a file for a scan.

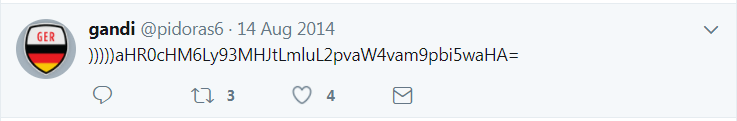

The link to an old and abandoned Twitter handle was a bigger mystery, until I decided to use the Advanced Search in Twitter and found this Tweet that must have been removed later on.

In base64, this Tweet says: https://w0rm.in/join/join.php. Unfortunately that site no longer resolves, but it used to be an underground board where website exploits were offered along with website hacking services around the same time the aforementioned Twitter profile was active.

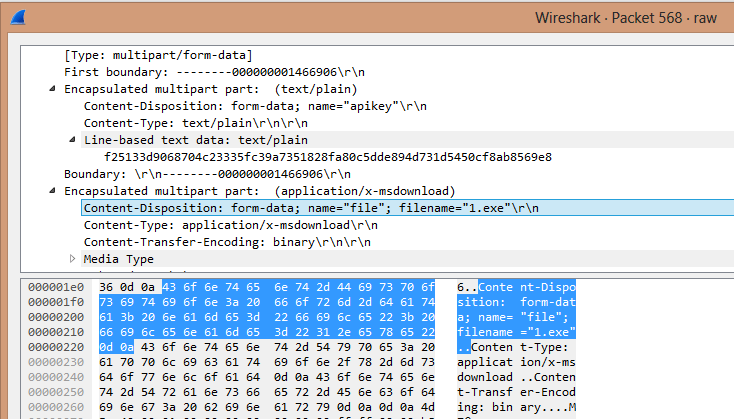

This was a dead end on trying to figure out what the malware was trying to GET. So we tried another approach by figuring out what it was trying to scan at VirusTotal and used Wireshark to take a look at the packets.

In the packet, you can see the API key and the filename that were used to scan a file at the VirusTotal site. So, reconstructing from the API calls and from the packets we learned that the malware was submitting copies of itself to VirusTotal, which is typical behavior for the Vflooder family of Trojans. Vflooder is a special kind of Flooder Trojan. Flooder Trojans are designed to send a lot of information to a specific target to disrupt the normal operations of the target. But I doubt this one was ever able to make a dent in the VirusTotal infrastructure. Or the one on Twitter for that matter.

The Vflooder Trojan is just a small and relatively simple example of analyzing API calls. It’s not always that easy: We’ve even seen malware that added redundant/useless API calls just to obfuscate the flow. But analyzing API calls is a method to consider for detecting malware trying to hide itself. Just keep in mind that the bad guys are aware of it too.